Torah says that if a man gets fed up with his wife, he can write her a severance document and they can be divorced – this is Deuteronomy 24:1-2,

Torah says that if a man gets fed up with his wife, he can write her a severance document and they can be divorced – this is Deuteronomy 24:1-2,

When a man takes a woman and is a husband to her, and it happens that she does not find favour in his eyes, or he finds something repulsive about her, he writes her a severance document and places it in her hand, and sends her forth from his house. And she leaves his house, and goes to another man.

The writing and delivering of the severance document is how a divorce is effected.

By the time of the Mishnah, we’ve started calling the document a get, גט (plural gittin). It’s an interesting word (the Gaon of Vilna observes) because it’s the only time those two letters appear together. In the whole Tanakh, gimel and tet never happen together. I think it’s the only word in the dictionary where they do. Appropriate for a word which is the essence of separation.

If you don’t have a get, you are still technically married even if you live separately, so if you get involved with another man you are in trouble because that is technically adultery and okay we don’t stone people today but it’s a fair bet that God’s going to be pretty annoyed. And if you go and have children by this other man, those children are in trouble; they are called mamzerim and they have an extremely limited and stigmatised ritual status.

So a get is important.

Since the Torah says “write,” many many laws of writing apply, as they do for the sifrei kodesh, Torah scrolls and so on, and since a get is so important, it’s important to get them right. Happily, the man is allowed to appoint an agent to do the writing for him, and he generally appoints a sofer.

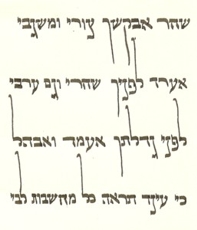

The writing is interesting; it’s quite a lot like Torah writing, but not exactly. There are a lot of issues with the text layout that you don’t get with a Torah, and a lot of rules connected with its being a legal document. The picture shows the sort of script. It’s not difficult if you’re accustomed to writing Torahs, but it’s unnatural – try typing with every letter T capiTalised, and you’ll see; you have To mainTain a differenT kind of focus.

The long letters are to prevent anyone coming along and writing extra bits between the lines afterwards. I’m not sure why there’s so much space between the lines; I assume it’s the conflation of two requirements: a) that the text be fitted into twelve lines b) the document must be longer than it is wide. Whence these requirements, I don’t know really.

The picture is actually part of a poem; because gittin are so important, we don’t noise them around. Unlike a ketubah, which you get to hang on your wall, a get is squirrelled away once it’s written, so as to reduce the potential for things to go wrong.

As with other sorts of important writing, the question of who’s allowed to do it comes up pretty early, but unlike a Torah, practically anyone’s allowed to write a get, according to the Mishnah. Gittin 2:5 says Anyone is kosher to write a get; even a deaf-mute, even a witless person, even a child. A woman may write her own get, and a man may write his own receipt, because the get is solely established by its signatories.